GRAVESEND, LONG ISLAND, NY, HISTORY

The History of Long Island,

from its earliest settlement to the present time.

Peter Ross.

NY Lewis Pub. Co. 1902

[transcribed by Coralynn Brown]

GRAVESEND

The English Town of Kings County - Lady Moody - Early Settlers and Laws - A Religious Community with a Sad Closing Record.

Among the towns of what is now Kings county, Gravesend for many years, in one respect, stood alone.

It was an English settlement, while the others were Dutch; it was no included in the aggregation known as the "Five Dutch Towns;" its interests seemed always on a different footing from theirs, and yet it was intensely loyal to the Dutch regime.

As to the origin of the name archaeologists have widely differed, and many a learned argument has been set forth in favor of some pet theoryh or other. Etymologists, more than any other class of students, have been guilty of weaving the most absurd theories, - so much so that a book on etymology ten years old is about as valuable, practically, as an ancient almanac; but they differ from all other classes of theorists by the remarkable good nature and equanimity with which they see their airy creations of words about words quietly thrown down.

Considerable time, patience and ingenuity have been spent to demonstrate that the name of this town was derived from 'S Gravesende (The Count's beach), after a place in Holland, but an equal amount of time, patience and ingenuity have been expended in endeavoring to prove that it was simply a transference of the name of the town of Gravesend in England.

Which of the two is right we will not attempt to discuss, for after all the question matters very little, - only we cannot help remarking that a great amount of argument and antiquarian anxiety would have been spared had some one of the early chroniclers quiety jotted down his views on the subject.

Another and more interesting argument among the local antiquaries has been caused by the effort to show that white men trod the soil of what afterward became Gravesend town long before a white face was seen on Manhattan Island or in Brooklyn, or even Flatlands. Indeed, we are told that Verazano, the Florintine navigator, who came here to explore the coastg and "see what he could see" on behalf of King Frances I, of France, in 1527, had anchored in Gravesend Bay; but the evidence on this point is not very clear, and has been the subject of much protracted and learned dispute.

Still it is not asserted that he effected a landing. He compared the harbor to a beautiful lake, and describes the boat-loads of red men which darted hither and thither on its surface. He did not investigate further, but seems to have sailed away in a northerly direction. As he passed out he saw natives gathering wampum on Rockaway Beach, and next discovered Block Island, whikch he called Louise, after the mother of King Francis.

In 1542 we read of another visitor, Jean Allefonsee, who reached the harbor after passing through Long Island Sound, and anchored off Coney Island; and we get glimpses of other navigators who seemed to thoroughly content with the beauties of New York's bay that they did not try to insitute any acquaintance with the land itself.

In September, 1609, however, Hendrik Hudson arrived in New York Bay and landed a boat's crew on Coney Island or thereabout, and there had a tussle with the natives and lost one of his men. So runs local tradition.

Across the bay, on the New Jersey shore, the local authorities have laid the scene of the tragedy at Sandy Hook, and built up a pretty strong theorectical argument in support of their claim. There is no doubt that Hudson landed several parties while in this vicinity and that he did not use the natives either courteously or kindly; and it is just as likely that a boat's crew from the "Half Moon" landed on the shores of Gravesend Bay as on any other place. The whole argument amounts to very little either way, and could the Gravesend theory be sutained, which it certainly cannot - neither can the Sandy Hook story, for that matter - its only result would be to give Gravesend in a sense a degree of superiority over her neighborhood as the scene where the white man made the imitiatory stepsh toward taking up his burden of converting that part of American to his own use and profit.

It may be well, however, to recall the name of the hero - perhaps he might be so called - who is recorded as having been the first white man to fall victim to Indian valor, or treachery, in the waters surrounding New York. He was an English sailor, John Colman, and he was killed, so we are told, by an arrow piercing his throat. His body was buried where it fell, the spot being long known as Colman's Point. But such legends are unsatisfactory, at the best, and we must come down to facts.

The earliest patent for land in Gravesend was issued to Anthony Jansen Van Sales, who has already been referred to at sufficient length in our notice of New Utrecht and elsewhere. This patent was dated May 27, 1643. On May 24, 1664, Gysbert Op Dyck, who emigrated from Wesel in 1635 and settled in New Amsterdam, where in 1642 he became Commissary of Provisions for the colony, obtained a patent for Coney Island. From Bergen's "Early Settlers of Kings County" we learn that "the present Coney Island was, on the first settlement of this county, composed of three islands, divided from each other by inlets or guts, now closed. The westernmost one was known as Coney Island, the middle one as Pine Island and the eastern one as Gisbert's Island, so named after Gisbert Op Dyck."

Here we run up against another etymological puzzle. What is the meaning of the word Coney? Thompson, who, by the way, identifies Pine Island as the scene of the Colman tragedy, tell us that the Dutch called it Conynen Eylandt, "probably from the name of an individual who had once possessed it." Others assure us that Conynen Eylandt is simply Rabbit Island, and they are probably right. Op Dyck never occupied the land covered by his patent, and seems to have held the property simply for a chance to sell it. This afterward led to pretty considerable trouble, involving the consideration and even the direct intervention of their High Mightinesses themselves.

There were doubtless settlers prior to 1643 in parts of what was afterward included in Gravesend townshiip, but if so their names have not come down to us. That year, however, was a memorable one in the annals of Gravesend, for then Lady Moody and her associates first settled there. They were, however, driven by the Indians from off the lands on which they settled by virtue of a patent issued that year, and went to Flatlands, where they remained until the redskins became more peaceable and amenable to reason. When Ladyship and her friends returned to Governor Kieft, on December 19, 1645, issued to them a second patent for the town of Gravesend, the first probably being lost in the turmoil of the times, and the patentees named included the Lady Deborah Moody, Sir Henry Moody, Bar., Ensign George Baxter and Sergeant James Hubbard.

This is the real beginning of the English town of Kings county, and Lady Moody ought to be regarded as its founder. She had a most interesting career, being a wanderer in search of civil and religious liberty at a time when aristocratic women were not much given to asserting themselves on such matters outside their own immediate households.

Deborah Moody was the daughter of Walter Dunch, a member of Parliament in the days of "Good Queen Bess." She married Sir Henry Moody, Bart., of Garsden, Wiltshire, who died in 1632, leaving her with one son, who succeeded to the baronetcy.

After Sir Henry's death her troubles began. In 1635, probably to hear the Word preached more in accordance with her own interpretation, than she possibly could in Wiltshire, and being a stanch noncomformist in religious matters, as well as a believer in the utmost civil liberty, she went to London and stayed there so long that she violated a statute which directed that no one should reside more than a specified time from his or her home. She was ordered to return to her mansion in the country, and it seems likely did so, for the Star Chamber had already taken action in her case and brooked no trifling with its mandates.

Probably she became a marked woman, and the watchful eye of the law was kept on her movements so steadily that, to secure liberty or worship and movement, she decided to emigrate. She arrived with her son at Lynn in 1640, and on April 5 that year, united with the church at Salem. On the 13th of May following she was granted 400 acres of land, and a year later she paid 1,100 lb for a farm. From all this there is every reason to believe that she intended making her home in Massachusetts. But she soon found out that true religious liberty, as she understood it, was not to be found in Puritan New England. A steadfast enquirer into religious doctrine, she became impressed with the views of Roger Williams soon after settling in Massachusetts, and his utterances concerning the invalidity of infant baptism appear to hve in particular won her adhesion. Being a woman who freely spoke her mind, she made no secret of the views she held, and her sentiments attracted much attention and drew upon her the consideration of the Quarterly Court. As Roger Williams had been thrust out of Massachusetts because of his views and his ideas on religious tolerance, Lady Moody's position could not be overlooked, and so, after being seriously admonished and it was apparent that she persisted in holding to her convictions, she was duly excommunicated.

Possibly in her case this might have ended the trouble, for she appears to have won and retained the personal respect of all her neighbors; but, being a high-spirited woman, she seems to have determined to seek still further to find the freedom for which she longed, and, to the surprise of all, removed her on and a few chosen and fast friends to New Amsterdam. Here she was warmly received by the authorities.

She met several Englishmen in the fort, among them being Nicholas Stillwell, who had, in 1639, a tobacco plantation on Manhattan Island, which he was compelled to abandon temporarily on account of the Indian troubles. He was quickly attracted by the idea of helping to found an English settlement where his fellow countrymen could not only mingle in social intercourse, but could unite to defend themselves whenever any need arose. He is said also to have been a believer in religious toleration and to have suffered persecution on that account in England; but the additional statement so often made to the effect that he had been forced to leave New England for the same cause is not born out by facts. He never saw New England.

Lady Moody, who had ample means (she retained her property in Massachusetts intact in spite of her removal), was regarded, singular to say, by Governor Kieft as a welcome addition to his colony, and he gladly gave her and her associates a patent for the unoccupied lands she, or some one for her, suggested, on which to form a settlement such as they desired.

At Gravesend Lady Moody was the Grand Dame, the real ruler. She enjoyed the confidence of Kieft and of Peter Stuyvesant to a marked degree, and although the latter was not over-fond of seeking the advice of women in affairs of state, he did not scruple to consult her on more than one occasion. He was entertained along with his wife at her house, and Mrs. Martha Lamb tells us that the Governor's wife was "charmed with the noble English lady." It has been claimed that lady Moody assumed the principles of the Society of Friends when that body first sought shelter on Long Island, but the evidence tends to show that she simply befriended and sheltered some of the primitive Quakers in accordance with her ideas of perfect religious freedom.

She seems to have remained at Gravesedn until the end of her life's journey, in 1659, the stories of her visiting Virginia, or Monmouth City, New Jersey, or other places, being without authentication. She found in Gravesend that degree of liberty in search of which she had crossed the sea, and was content to pass her days in its congenial atmosphere.

Of her son, Sir Henry, little is known. He left Gravesend in 1661 and went to Virginia, where he died.

Lady Moody's library was famous and it is through her son's departure for Virginia so soon after her death that we are enabled to judge, to a considerable extent, of its contents. To the notarial "Register" of Solomon Lachaire, of New Amsterdam, we are indebted for the following list under date of 1661.

As it is not likely that the baronet carried any of the books with him on his travels, it is safe to assume that the list of Lady Moody's literary treasures is here given complete:

Cathologus containing the names of such books as Sir. Henry Moedie had left in security in handts of Daniel Litscho wen by went for Virginina:

- A latyn Bible in folio.

- A written book in folio containing privatt matters of State.

- A writteneth book in folio conining private matters of the King.

- Seventeen several books of devinite matters.

- A dictionarius Latin and English.

- Sixteen several latin and Italian bookx of divers matters.

- A book in folio contining the voage of Ferdinant Mendoz, &c.

- A book in folio kalleth Sylva Syvarum.

- A book in quarto calleth bartas' six days worck of the lord and translat in English by Joshuah Sylvester.

- A book in quarto kalleth the Summe and Substans of the Conference which it pleased his Excellent Magsti to have with the lords bishops &c. at Hampton Court contracteth by William Barlow.

- A book in quarto kalleth Ecclesiastica Interpretatio, or the Expositions upon the difficult and doubtful passage of the Seven Epistles called Catholique and the Revalation collecteth by John Mayer.

- Elleven several bookx moore of divers substants.

- The Vertification of his fathers Knights order given by King James - Notarial Reg. of Soloman Lachaire N. P. of New Amsterdam, Anno 1661.

In many respects the patent issued by Governor Kieft to Lady Moody was peculiar. It was the only one extant in which the patentees were headed by a woman, and it contained such full powers for self-govenment and for the enjoyment of freedom of religion as to be unique among the patents signed by Keift or his successor, Stuyvesant. For these reasons the patent is here presented in full as printed in the "Documentary History of New York," vol I, page 629:

Whereas it hath pleased the High & Mighty Lords the Estates Genl of the United Belgick Provces - His Highness Frederick Hendrick by ye grace of God Prince of Orange, &c. and the Rt. Honourable ye Lords Bewint Hebbers of the W. I. Company by theyr several Commissions under theyr hands and seales to give and grant unto me Wm Kieft sufficient power and authorities for the geneal rule & gouverment of this Province called the New Netherlands, & likewise for ye settling of townes, collonies, plantations, disposed of ye land within this province, as by ye said Commissions more att large doth and maye appeare, Now Know yee whomsoever these Presents may any ways concerne that I, William Kieft, Gouvernor Generall of this Province by vertue of ye authoritie abovesaid & with ye advice & consent of ye Councell of State heere established have given and graunted & by virtue of these presents doe give grant & confirme unto ye Honoured Lady Moody, Sr Henry Moody Barronett, Ensign George Baxter & Sergeant James Hubbard theyr associates, heyres, executors, administrators, successours, assignes, or any they shall join in association with them, a certaine, quantitie or p'cel of Land, together with all ye hauens, harbours, rivers, creeks, woodland, marshes, and all other appurtenances thereunto belonging, lyeing & being uppon & about ye Westernmost parte of Longe Island & beginning at the mouth of a Creeke adjacent to Coneyne Island & being bounded one ye westwards parte thereof with ye land appertaining to Anthony Johnson & Robt Penoyer & soe to run as farre as the westernmost part of a certain pond in an ould Indian field on the North side of ye plantatioln of ye said Robbert Pennoyer & from thence to runne direct East as farre as a valley beginning att ye head of a flye or Marshe sometimes belonging to ye land of Hughe Garrettson & being bounded one the said side with the Maine Ocean, for them the sd pattentees, theyr associates heyres, executors, adminisrs, successours, assigns, actuallie reallie & perpetuallie to injoye & processe as theyr owne free land of inheritance and to improve and manure according to their owne discretions, with libertie likewise for them the sd pattentees, theyr associates, heyres, and successours and assignes to put what cattle they shall think fitting to feed or graze upon the aforesd Conyne Island, forther giving granting & by vertue of these presents Wee doe give & graunt unto the sd Patentees theeir associates heyrs & successours full power & authoritie uppon the said land to build a towne or townes with such necessarie fortifications as to them shall seem expedient & to have and injoye the free libertie of conscience according to the costome and manner of Holland, without molestation or disturbance from any Madgistrate or Madgistrates or any other Ecclesiasticall Minister that may p'tend jurisdiction over them, with libertie likewise for them, the sd pattentees, theyr associates heyres &c to erect a bodye pollitique and civill combination amongst themselves, as free men of this Province & of the Towne of Gravesend & to make such civill ordinances as the Maior part of ye Inhabitants ffree of the Towne shall thinke fitting fot theyr quiett & peaceable subsisting & to Nominate elect & choose three of ye Ablest approved honest men & them to present annuallie to ye Governor Generall of this Province for the tyme being, for him ye said Governr to establish and confirme to wch sd three men soe chosen & confiremd, wee doe hereby give & graunt full power & authoritie, absolutelie & definitevely to determine (wthout appeal to any superior Court) for debt or trespasse not exceeding ffiftie Holland Guilders ffor all such actns as shall happen within ye jurisdictn of the above said limit with power likewise for any one of the said three to examine uppon oath all witnesses in cases depending before them & in case any shall refuse to stand to the award of what the Maior part of the sd three shall agree unto, in such cases wee doe hereby give and graunt full power and authoritie to any two of ye sd three, to attache & ceise uppon ye lands goods, cattles and chattles of ye parties condemned by their said sentence & fourteen days after the sd ceizure (if ye partie soe condemned agree not in the interim & submitte himself unto ye sentence of the sd three men) the said three or three appointed men as afforsd to take or ioyen to themselves two more of theyre neighbours, discreete honest men, and wth the advice of them to apprise the lands, goods, cattles & chattles wthin the above sd jurisdictn & belongs to the partie condemned as aforesd to ye full valleu & then to sell them to any that will paye, that sattisfaction & paiement may be made according to the sentence of ye appointed men: Likewise giving & graunting & by virtue hereof wee doe give & graunt unto ye said Pattentees, theyre assocates heyres, successours &c. full power & authoritie to Elect & nominate a certaine officer amongst themselves to execute the place of a Scoute & him likewise to present annuallie to the Governor Generall of this Province to bee established and conprmed, to wch sd officer soe chosene confirmed, Wee doe hereby give & graunt as large & ample power as is usuallie given to ye Scoutes of any Village in Holland for the suppression or prevention of any disorders that maye theyr arise, or to arrest and app'hend the body of any Criminall, Malefactouer or of anye that shall by worde or act disturbe the publick tranquilletie of this Province or civill peace of the inhabitants within the above sd jurisdictn & him, them & her so arrested or apprehended to bring or case to be brought before the Governor Genll of this Province & theyre by way of Processe declare against the P'tie soe offending; farther Wee doe give & graunt unto the P'tentees theyr associates heyres &c free libertie of hawking, hunting, fishing, fowling within the above sd limitts; & to use or exercise all manner of trade & commerce according as the Inhabitants of this Province may or can be Virtue of any Priviledge or graunt made unto them, indueing all and singular ye sd pattees theyr associates, heyre &c with all & singular the immunities & priveledges allready graunted to ye Inhabitant of this Provce or hereafter to be graunted, as if they were natives of the United Belgick Provinces, allways provided the sd pattentes yr associates heyres &c shall faithfully acknowledge & reverently respect the above named High Mightie Lords &c for theyr Superiour Lords & patrons & in all loaltie & fedelltie demeane themselves toward them & theyr successours accord'g as the Inhabitants of this province in dutye are bound, soe long as they shall [be] within this jurisdictn & att the expereatn of ten yeares to beginne from the daye of the date hereof to paye or cause to be paid to an officer thereunto deputed by the Governr Genl of this Provc for the time being, the tenth parte of the reveneew that shall arise by the ground manured by the plow or howe, in case it bee demanded to bee paid to the sd officer in the ffield before it bee housed, gardens or orchards not exceeding one Hollands acre being excepted, and in case anye of the sd pattentees theyr associats heyres &c shall only improve theyr stocks in grasing or breeding of cattle, then the partie soe doing shall att the end of the ten years afforesaid paye or cause to be paid to an officer deputed as aforesd such reasonable sattisfactn in butter and cheese as other Inhabbats of other townes shall doe in like case: Likewise, injoyning the said pattentees theyr heyres &c in the dating of all public instruments to use the New Style wth the wts & measure of this place.

Given under my hand & Seale of this Province this 19th of December in the fort Amsterdam in New Netherland. 1645.

Signed .. Wilhelm Kieft.

Endorsed, - Ter ordonnatie van de Hr Directr Genereal & Raden van Nieuw Nederlandt.

Cornelius Van Tienhoven,

Secretary.

The only fault to be found with this document was the loose way in which the boundaries were set forth. This was amended to a certain extent in the patent issued in 1670 by Gov. Lovelace, and the limits were still more closely defined in Gov. Dongan's patent, issued in 1686.

In the latter document the quit rent to be paid by the town was fixed at "six bushels good winer merchantable wheat," a tax that was felt to be comparatively light, and therefore - as is usual in such circumstances - just and equitable.

On being armed with Kieft's patent Lady Moody and her friends lost no time in proceeding to the land awarded them and beginning operations by laying out a town site. Concerning this the late Rev. A. P. Stockwell wrote:

In view of the natural advantages which the town possessed, they no doubt hoped to make it, at some future day, a large and important commercial center. From its situation at the mouth of "The Narrows," and with a good harbor of its own; with the ocean on the one side, and the then flourishing village of New Amsterdam (New York) on the other, there did indeed seem to be good ground for such an expectation. But unfortunately, as the event proved, Gravesend Bay, though affording secure anchorage for smaller craft, would not permit vessels of large tonnage to enter its quiet waters with perfect safety; and so the idea of building a "city by the sea," which in extent, wealth, and business enterprise, should at least rival New Amsterdam, was reluctantly abandoned.

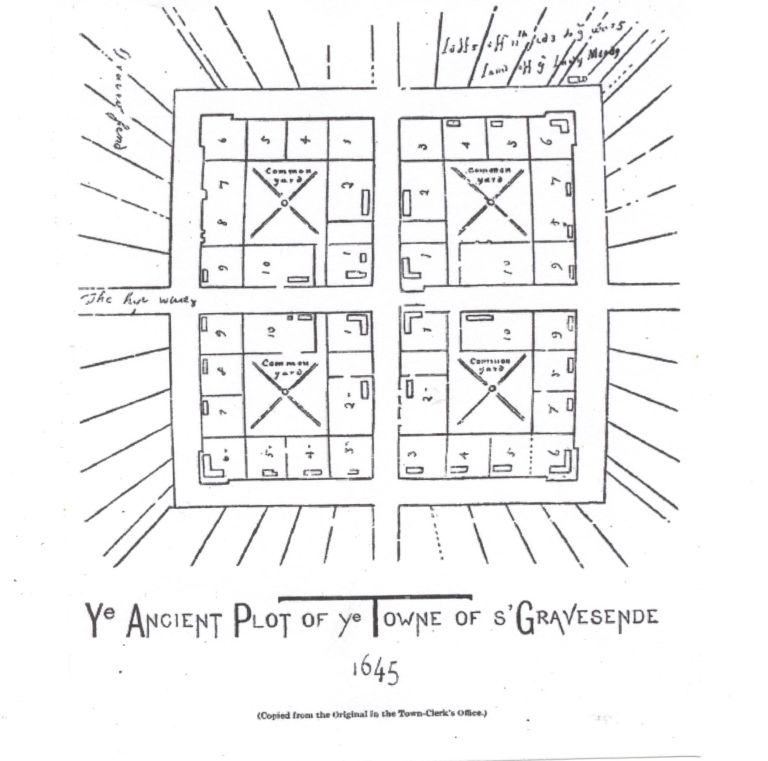

However, with this end in view, as the work begun would seem to indicate, they commenced the laying out of the village. Selecting a favourable site near the center of the town, they measured off a square containing about sixteen acres of ground, and opened a street around it. This large square they afterwards divided into squares of four acres each, by opening two streets at right angles through the center. The whole was then enclosed by a palisade fence, as a protection, both against the sudden attacks by hostile Indians, and the depredations of wolves and other wild animals which were then common upon the island.

Upon one of the oldest maps of the town, on file in the clerk's office, we find a perfect representation of the village-plan as originally laid out. From this we learn that each of the four squares was divided into equal sections, laid off around the outside of each square and facing the outer street. These were numbered from one to ten, in each of the four squares. This gave forty sections in all; and thus one section was allotted to each of the forty patentees. By this arrangement every family could reside within the village, and share alike its palisade defence. In the center of each square was reserved a large public yard, where the cattle of the inhabitants were brought in from the commons, and herded for the night for their better protection. At a later period, if not at this early date, a small portion of each square was devoted to public uses. On one was the church, on another was the school-house, on another the town's hall, and on the fourth the burying ground. The farms, or "planters' lots" as they were then called, were also forty in number, and were laid out in triangular form with the apex resting in the village and the boundary lines diverging therefrom like the radii of a circle.

From the fact that the village was divided into forty lots and that forty farms radiated therefrom, we have naturally inferred that there were forty patentees. If this be so, one of them very early in the history of the town must have dropped out of the original number, either by death or removal, or, as tradition has it, forfeiting by his profligate life all his right, title, and interest in the property allowed to him.

It seems, however, from the records that only twenty-six persons up to 1646 had settled with Lady Moody in Gravesend and taken part in laying out the town, and that the full quota of forth according to the plan was filled up by subsequent arrivals.

The first troubles met with came from the Indians, who appear to have held rather obnoxious views as to the settlement from the first. Every man was ordered to be armed and equipped to meet a possible, even probable, attack at any moment, and was also required to keep a certain part of the pallisade surrounding the town in thorough repair. When the palisadw was being built in 1646 an attack was made unexpectedly, and the best the settlers could do was to escape to Flatlands. Lady Moody's house, probably because it was the most conspicuous in the settlement, was most frequently marked out for attack, and Nicholas Stillwell, who seems in time of such trouble to have assumed command, had a difficult task in repelling the savage warriors.

The townspeople for a time became despondent over the outlook. Stillman himself returned to New Amsterdam and saw no more of Gravesend until 1648, when he bought a town plot, and even Lady Moody had serious thoughts of going back to her property in New England. But a peace was finally patched up between Gov. Kieft and the Indians and Gravesend was allowed to take up the thread of its story without more trouble.

Another Indian incursion, the last on record, took place in 1655, when a fierce attack was made on the town; but although the settlers could not drive the foe away, on account of their numbers, they made a gallant defense behind their palisade and kept the red-skins at bay until relieved by a force of military from New Amsterdam. From the first the settlers, according to their lights, tried to deal honestly with the aboriginal owners of the soil. Even before Keift's second patent was issued in December 1645, they had secured by purchase a deed from the Indians, and in 1650 and 1654 they secured other deeds covering the land on Coney Island.

In 1684, when all trouble was at an end, they secured another deed from the red men, for all the lands in Gravesend, in exchange for "one blanket, one gun, one kettle." Surely the principle of fail dealing could go no further!

The municipal history of Gravesend began almost with its settlement. In 1646 the first three "approved honest men" elected as Justices were George Baxter, Edward Brown and William Wilkins; Sergeant James Hubbard was elected Schout; and John Tilton (who had accompanied Lady Moody from New England) was chosen to be Town Clerk. All these elections were approved by the Governor. Town meetings were held monthly, and at one, held Sept. 7, 1646, it was decreed that any holder of a lot who by the following May had not erected a "habitable house" on it should forfeit the lot to the town. Such matters as the repair of the palisade, registry of what are now called vital statistics, the defense of the town, the morals and habits of its citizens, and the humane care of live stock, were the subjects most generally discussed. All the inhabitants were compelled to attend these town meetings when summoned by the beating of a drum or the blowing of a horn. Infractions of the laws were tried before justices and the penalties at first were fines which were for a time put into the poor fund, but after 1652 were placed in the treasury for general purposes, In 1656 the people passed a stringent liquor law which prohibited entirely the sale of "brandie, wine, strong liquor or strong drink" to any Indian, under a fine of fifty guilders for a first offence and double that amount for a second. No more than a pint was to be sold, at one time, even to white people. This law was rigidly enforced in spite of the difficulty of proving its violation.

The laws regarding the preservation of the sanctity of the Sabbath, as might be expected, were very rigid. It seems strange to record the fact that at one time in Gravesend a town meeting ordered a bounty of five guilders to be paid for every wolf killed in the township. The town court attended to all petty criminal or civil cases, but the criminal cases were comparatively few, and slander and assault seemed to be the prevailing weaknesses of the more demonstrative citizens.

In 1650, for these decadents, as well as for petty thieves, the stocks were brought into requisition and continued a favorate mode of punishment until the ninteenth century was well advanced.

In 1668 the town received quite a boom by the settlement in it of the Kings County Court of Sessions which had previously met in Flatbush. This body continued to dispense justice in Gravesend until 1685, when it returned to its former home.

It is singular that in an essentially religious community like Gravesend, and a community the earlier records of which are more complete and methodical than those of any other town in Kings county, there should be any dubiety about its first place of worship; but such is the case. An effort has been made to show that a Dutch Reformed Church, or congregation, was established in 1655, and the church now existing of that body claims a history dating form 1693; but both these dates are manifestly wrong. In 1655, and even in 1692, the Dutch was the language used in the service of that body, and we must remember that Gravesend was an English community. In 1657 Dominie Megapolensis, in a report to the Classis of Amsterdam, said that at Gravesend they reject "infant baptism, the Sabbath, the offic of preacher and the teachers of God's Word, saying that through these have come all sorts of contention into the world. Whenever they meet together the one or the other reads something to them."

These were very probably Lady Moody's own views and show why no early church was founded in the settlement at all. In 1657 Richard Hodgson and several other Quakers reached Gravesend and were kindly received, but there is not the slightest reason for supposing that Lady Moody adopted all of their tenets and became a member of the Society. That would have been a departure from her own First Principles and she was not the sort of woman to make such a change. That the Quakers found a resting place at Gravesend is certain; it was founded on just such a refuge; and in 1672, when George Fox was on his American tour, he also stopped at the town, where he found several of his people and held "three precious meetings." But it was not a Quaker settlement, nor, like Flatbush, a Dutch Reformed settlement. There is no mention in the records of the church at Flatbush of a congregation at Gravesend until 1714, though it is possible that for many years before some of the citizens attended worship in Trinity Church in New York, and that the authorities there, at intervals, sent over a clergyman to hold services in the town.

From 1704 there is evidence that the ministers at Flatbush considered Gravesend part of their bailiwick and receipts were formerly extant showing that Gravesend paid a share of the Domonie's salary from 1706 to 1741. In 1714, after Dutch had ceased to be the sole language used in the Reformed Churches, an agreement was entered between the people of Gravesend and the church at New Utrecht for a share in the services of the ministers who visited the last named town. It is probable that when this short-lived arrangement went into effect a church building was erected. It seems certain that one was in existence in 1720, when it was called "the meeting-house" and was apparently ready to house a preacher of any demonination who came along.

The Rev. Mr. Stockwell, who patiently investigated this subject, did not believe that any separate congregation of any religious body was organized in Gravesend prior to 1673. That body was the Reformed Church, and as the records were kept in Dutch until about 1823 we may readily understand that the English-speaking citizens had little share in its foundation or in its progress.

In 1763 a new meeting-house was built on the site of the first one, a little oblong building with high pitched roof, surmounted by a belfry. Inside was a plain box-like pulpit with a huge sounding board. Underneath one side of the gallery was the negro quarter, reserved solely for the use of the colored brethren.

"This old church," wrote Mr. Stockwell, "within the memory of those now living was without stoves or any other heating appliances. The women carried foot-stoves, which, before service, they were very careful to fill at the nearest neighbor's, while the men were compelled to sit during the long service with nothing to generate heat but the great Calvinistic preaching of the Dutch dominie, or the anticipation of a warm dinner after the service was over!"

Whitefield preached twice in this little tabernacle, which continued in use until 1833, when it gave way to a more modern structure, which, with many imporvements, is still in use.

In 1767 Martinus Schoonmaker became pastor of the little congregations in Harlem and Gravesend, receiving as salary from the last name 35lb a year and preaching at frequent intervals. In 1783 he became minister of the Collegiate Church, with his headquarters at Flatbush, and after that held services in Gravesend once in each six weeks, and Gravesend continued to be part of the care of the Flatbush ministers until 1808, when the Collegiate arrangement ceased. It was not until 1832, however, that the Gravesend church acquired a settled pastor, and in that year the Rev. I. P. Labagh was installed. In 1842 he was suspended from the ministry for refusing to recognize the authority of the Classis, and for holding opinions unorthodox, and the Rev. Abram I. Labagh was installed in his place. This pastorate continued for seventeen years, and in 1859 the Rev. M. G. Hanson was called to the pulpit. He resigned in 1871 and a year later the Rev. A. P. Stockwell was called. This gentleman devoted much care to the study of the civil and ecclesiastical history of Gravesend, and to a sketch from his pen the present chapter of this work has been greatly indebted.

He continued to minister to this church until 1886 when he retired and devoted himself mainly to literary work until his death in Brooklyn, in 1901. He was followed in the ministry of Gravesend by the Rev. P. V. Van Buskirk, who still remains the charge, and who has labored most successfully and won the love of his large and steadily growing congregation, as well as of the entire community in which he has ministered so long and so faithfully.

We have seen that in one of the squares in the original plan of Gravesend a place was laid aside as a burying ground, and it was probably used as such when occasion required. The earliest record extant, however, concerning this now venerable God's-acre is contained in the will of John Tilton, dated Jan. 15, 1657, in which he devised land "for all person in ye Everlasting truthe of ye gospel as occasion serves for ever to have and to make use of to bury their dead there." It is thought that the land thus deeded adjoined the original burying ground and Tilton's bequest was in reality an addition and at once incorporated within its boundaries. It was probably part of the original lot, which Tilton received when he settled at Gravesend with Lady Moody. the oldest stone extant now bears the date of 1676, and many of the inscriptions discernible are in Dutch. One plain rough stone, hardly readable, was thought by Teunis C. Bergen to mark the grave of Lady Moody; but this was merely an antiquary's facny. From the formation of Greenwood Cemetery the Gravesend burial ground began to fall into disuse and interments in it have now practically ceased.

There is another burying ground in the townhip - Washington Cemetery - laid out in 1850 and inclosing about 100 acres, which is mainly used by Hebrews.

Regarding the dwellings which early existed in Gravesend, the Rev. Mr. Stockwell said:

It may be interesting to know the style of house which afforded shelter and protection to the early settlers. If the following is a fair specimen, it will not strike us as being too elaborate or expensive, even for that early day. Here is the contract for a dwelling, as entered by the town-clerk upon his record:

"Ambrose London bargained and agreed with Michah Jure for his building him a house by the middle of June nexte, and to paye the said Michah 40 gilders for it - at the time he begins a skipple of Indian corne, at the raising of it 10 guilders, and at ye finishing of it yet the rest of said summ. Ye house, to be made 22 foote long, 12 foot wide, 8 foote stoode with a petition in ye middle, and a chimney, to laye booth rooms with joice, to cover ye roof, and make up both gable ends with clabborads, as also to make two windows and a door."

This man, London, was rather a speculator, and soon disposed of this house, and made another contract for a larger and still more commodious one; the contract price for building it being $44. John Hawes was the builder and his contrat was to build "1 house framed uppon sills of 26 foote long, and 16 foote broad and 10 foote stoode, with 2 chimneys in ye middle and 2 doors and two windows, and to clabboard only ye roof and dobe the rest parte." The price was 110 gilders, or instead, "one Dutch cow."

But, if their homes were built more with reference to their comfort and actual necessities than for display, the same was true of their household furniture and personal effects, as will be seen from the following inventory of the estate of John Buckman, deceased, dated in the year 1651, and signed by Lady Moody as one of the witnesses.

Among a few other articles appear the following:

"1 Kettle, 1 Frying Pan, 1 Traye, 1 Jarre, 1 pair breeches, 1 Bonett, 1 Jackett, 1 Paile, 2 shirts, 1 Tubbe, 1 Pair shoes, 2 pair ould stockings, 9 ould goats, money in chest, 32 gilders."

The first roads to these houses were mere wagon paths, rough and unkempt, although the roads, or streets inside the palisades in the town square, appear to have been well kept, and were regarded as the best to be seen anywhere. The outer roads were made simply by merely clearing away the brush, and their boundaries were kept defined mainly by the traffic. At times, however, the town meeting took a hand in their improvement, as in 1651, when it was agreed that "every inhabitant who is possessed of a lot shall be ready to go by the blowing of ye horn on Thursday next to clear ye common ways."

In 1660 a highway was laid out from the town to the beach. By 1696 Gravesend was connected with Flatbush and Flatlands and New Utrecht by rough but servicable roads, and King's Highway, still extant among a wilderness of new streets, was laid out about the same time.

Nothwithstanding all its advantages of magnificent soil, a settled community, perfect freedom of conscience and proximity to the even then great commercial centre, the progress of Gravesend was slow. It had, it would appear, at one time some pretentions to commercial dignity on its own accord, for in 1693 it was declared one of the three ports of entry on Long Island; but even with this distinction it continued to make tardy progress. In 1698 its population was only 210, including 31 men, 32 women, 124 children, 6 apprentices and 17 negroes. By 1738, forty years later, the total number had increased to 368, of which 50 were negroes. In 1790 it boasted 294 whites and 131 negroes. Probably when the Revolutionary War broke out it contained in round numbers a population of 350, white and colored.

That war, in the case of the other towns in Kings county, may be said to mark the central point of the history of Gravesend. Many of the troops were landed on its ocean front on that memorable morning in August 1776, when the British movement began. It was supposed that from its English antecedants, Gravesend would be even more pronouncedly Tory in its sentiment than the other towns in its part of Long Island; but the opposite seems to have been the case. In the battle of Aug. 27th the Patriot fighters from Gravesend are said by the local historians to have given a good account of themselves, although their losses were small as their knowledge of the country enabled them to escape from the defeat and return to their homes in safety, while others who escaped in the melee were captured or killed by roving bands of the enemy. The tide of war soon carried the troops away from Gravesend.

But during the entire British occupation of the island the town was in a condition of perpetual trouble and excitement. Prisoners and soldiers were billeted upon the people without ceremony, the soldiers robbed with apparent impunity and lawless bands of thieves made frequent descents upon farmhouses and stripped them of their valuables and provender. It was truly a reign of terror for peace-loving people while it lasted, and Patriot and Tory seemed to have suffered alike from the horrors of military rule. That the people were peaceably disposed is very evident from the fact that several of the Hessian soldiers remained in Gravesend after peace was declared and assumed all the duties of citizenship, and, it is said, with credit to themselves.

On October 20, 1789, General Washington, then President, visited Gravesend and held a sort of levee in the town square. As might be expected he was devotedly welcomed and with his visit we may consider the early history of Gravesend fittingly brought to an end.

Having thus presented the leading facts in the opening annals of Gravesend, the story of a particular section which to a certain extent has always maintained a separate history, and the name of which is known throughout the civilized world, even in places where Long Island's Gravesend was never heard of, may here be fittingly considered. This is the famous Coney Island, the first disposal of which to a white man has already been mentioned in this chapter. Op Dyck tried to realize on his purchase by selling his eighty-eight acres of sand dunes, brush and waterfront to the Gravesend people in 1661, but they declined to purchase, alleging that it was theirs already by right not only of their town patent but by a deed of purchase in 1649 from Cippehacke, Sachem of the Canarsies (in which the island was called Narrioch), and also of another deed, dated May 7, 1654, in which (in exchange for 15 fathoms of seawant, 2 guns, and 2 pounds of powder) they obtained from the Nyack Indians, who claimed to be the real owners, not only a conveyance of Coney Island, but a strip along the shore near the old village of Unionville, which afterward involved the town in such vexatious litigation. Failing thus to dispose it of, Op Dyck sold his claims to Derick De Wolf, the transfer bearing date October 29, 1661. In the following year De Wolf, who had obtained from the West India Company in Amsterdam a monopoly for the manufacture of salt in New Netherland, erected his plant on the island and commenced operations. Incidentally he warned the Gravesend folks to cease from pasturing their cattle on Guisbert's Island, or using it for any purpose. This so enraged these usually quiet and peaceable citizens that they marched to the island, overrun the establishment, tore down the palisade and manufactory and made a bonfire of their ruins, and threatened to silence the remonstrations of the man in charge by throwing him on top of a burning pile. This put a stop to the enterprise; and, although De Wolf sent a remonstrance to Amsterdam and their High Mightinesses ordered Stuyvesant to protect the sale-maker in his rights, the Governor did nothing in the matter. In fact, he openly took the side of the Gravesend people in the dispute, and so the trouble continued until the advent of Governor Nicolls wiped out the monopoly.

In Governor Lovelace's charter, or patent, issued in 1671, the right of Gravesend to the island was clearly set forth. Still there seems somehow to have remained a doubt, and in 1684 a new conveyance was obtained from the Indians and the whole was placed beyond any pretence of future question by the terms of Governor Donegan's patent of 1685, and Coney Island continued to be a part of the territory of Gravesend until the town government itself was wiped out of existence by the Moloch-like march of modern improvement.

The island's destinies being then so far settled, it was, in 1677, laid out in thirty-nine lots of some two acres each, and so divided among the people. They agreed to fence it in and plant it only with "Indian corn, tobacco or any summer grain," and when not so used it was to be in common a feeding place for cattle.

The Labadist Fathers, who visited Coney Island in 1679, have left the following record:

"It is oblong in shape and is grown over with bushes. Nobody lives upon it, but it is used in winter for keeping cattle, horses, oxen, hogs and others, which are able to obtain there sufficient to eat the whole winter and to shelter themselves from the cold in the thickets."

It continued to be used mainly for feeding cattle either in common or by lease down to about 1840, when its modern history may be said to begin.

The people of Gravesend, however, seem to have been careful to retain in their own hands and for their common use many of the privileges of ownership, such as fishing, hunting, the use of timber and common rights of pasturage to unenclosed places.

The history of Gravesend from the time of Washington's visit until about 1870 might be characterized by the tern "reposefulness." In fact, its people might be said to have dwelt by themselves and for themselves and to have let the world roll along, unmindful of how it rolled so long as its commontions did not shake them off. Human nature now and again asserted itself around election times, when the citizens shouted their preferences, but when the election was over the men, then as now, wondered what they really had been shouting for, and what difference the result made to them. There was marrying and giving in marriage, children were born, educated at the village shcool to the best of its ability, and then stepped into their fathers' shoes; or if there were many sons in a household each managed to secure a bit of farm land in the township and settled down to start a new branch of the family, and the little cemetery, even with Tilton's pious addition, was steadily being filled up. So far as we have been able to judge, few Gravesend boys, compartively, left the township to seek their fortunes in the outer world.

Within it there was at least an abundance, and if it had no millionaires it had no paupers, and by paupers I mean men or women who have fallen by the wayside in the struggle of life as a result of their own waywardness or worse.

Early in the ninteenth century we read of a new road being occasionally opened, making transit to the beach or to the other townships easy, and now and again we come across stories of amateur fishermen from the outside world who discovered its shore and spent a few days now and again, to return to their homes with stories of wonderful success, generally justified in their cases by truth. The court records show an intricate bit of litigation now and again over some boundary question, of little or no interest now that boundaries have been swept away; while the church continued a matter of prime interest in the community and the real center of its civil and social as well as its religious life.

These brief sentences really sum up the history of Gravesend for the half century or so that passed from the time the last British troopship sailed out of the Narrows until what might be called the modern awakening set in. A glance at the population returns helps to emphasize all this. In 1800 its figures were 517, and ten years later 520, a gain of 3. By 1835 it had increased to 695, and to 951 according to the State census of 1845.

Some might begin the modern story of Gravesend from around the last date on account of the religious activity which then sprang up. The Third Reformed Church edifice was dedicated in January, 1834, a paronsage was built in connection with it in 1844, and a chapel and meeting house was erected in 1854, covering the site of the pioneer church. In 1840 a Methodist Episcopal Church was organized at Sheepshead Bay, under the name of the Methodist Protestant Church, and although that particular designation has long been abandoned it still carries on its work. In 1844 another Methodist Episcopal Church was organized at Unionville.

From the church to the school is an easy transition, for in most of our early records, the two almost followed each other so closely that their beginnings might be said to be contemporaneous. In Gravesend, however, it is not until 1728 that we find evidence of a school-house, when a deed shows that on April 8 of that year "one house and two garden spots" were sold for 19lb by Jacobus Emans to the freeholders for the use of a school "and for no other use or employment whatsoever." This purpose, however, was not carried out to the letter, for the site thus laid apart for educational purposes was that on which, in 1873, the town hall was erected. It is hardly to be imagined, however, that no provision for education existed in Gravesend prior to 1728, and it is likely that as soon as the need appeared a teacher found employment and a place for teaching, even although, as elsewhere on Long Island, he migrated from house to house.

The building erected on the Emans "lots" served as school-house until 1788, when a larger structure was erected on the same site. This continued to be the local school-house until 1838, when another site, singular to say, from another representative of the Emans family (Cornelius), was purchased and a commodious building erected which afterward was known as District School No. I, and so continued until annexation. Gravesend is now as well equipped with educational facilities as any section of Greater New York, while its private schools have won many tributes of praise for their high standing and efficiency.

The modern progress of Gravesend may be traced as clearly by the extension of its roads as by any other basis, for its progress in this regard was slow and gradual and strictly in keeping with absolute necessity. It is only within recent years that the construction of public thoroughfares began to be undertake before there was developed a crying demand for them. In 1824 what was known as "Coney Island Causeway" was laid out from Gravesend to the ocean front, virtually a continuation of an old road through the village, and although somewhat primitive it continued to be a toll road, paying a dividend to its stockholders, until 1876, when it was sold to the Prospect Park & Coney Island Railroad. In 1838 a free road was begun from Gravesend to Flatbush, a continuation inland of the road to the sea.

In 1875 the road was widened to 100 feet and extended to the Brooklyn city line, receiving the name of Gravesend avenue. It proved from the first the main artery of trade and travel. The Coney Island Plank Road, laid out and partly opened for traffic in 1850, which extended from Fifteenth street, Brooklyn, to Coney Island, was long the principal carriage road to the shore. The planks were removed after ten years service. In 1871 an effort was made to improve this road, but while the story is one of most disgraceful in local politics, it is hardly worth while to enlarge upon it now. Many other roads were surveyed and several were opened up between 1865 and 1876, and was a popular thoroughfare from the beginning. It was an honest piece of work throughout, and showed the citizens how economically an improvement could be effected when undertaken by business men and carried out on business principles.

But all these roads fade into insignificance when compared with that magnificent accomplishment, the Ocean Parkway, which was begun in 1874 and completed in 1880. It is five and one-half miles long, with a width of some 210 feet, and is one of the most perfectly appointed and best equipeed roads in the world. Its main purpose is pleasure, and its appearance on a spring or autumn afternoon, crowded with richly appointed vehicles and pleasure carriages of all sorts, bicycles, automobiles, as well as pedestrians, is not to be found surpassed, if equalled in all desirable respects, by the boulevards of Paris. It is one of the many enduring monuments to the late T.J.T. Stanahan, who is generally considered to be the oroiginator of the idea of constructing such a magnificent parkway.

One feaure which added to the material progress of Gravesend was the introduction of horse-racing, which may be said to have commenced in 1868 with the incorporation of the Prospect Fair Grounds Association. This body of "horse lovers" bought a tract of some sixty acres near Gravesend avenue, built a club house and laid out a track. The association afterward removed to Ocean Parkway. Another track was laid out at Parkville. These were comparatively private affairs and did not prove profitabe to those who find profit in horse-racing. In 1880, however, a bold bid for public favor was made by the Coney Island Jockey Club, which secured about one hundred and twenty-four acres of land near Sheepshead Bay, ladi out a splendid track, adapted the grounds throughly to meet the wants of large gatherings of people, built a commodious grand-stand, stables, out-houses, etc., and the enterprise at once sprang into popular favor. It was not long before the "race days" became events, and attracted crowds of all classes from New York, Brooklyn and even more distant places. Since then the Brooklyn Jockey Club has established a course at Gravesend and the Brighton Beach Racing Association another at Coney Island. They have their ups and downs, it seems to us, in public favor, but all manage to secure more or less patronage and more than meet the demand for the "sport of kings," as it is called, in the section of Long Island in which they are located. All these institutions have helped to build up Gravesend and to aid in its financial prosperity. Whether they have aided in moral progress, whether they have brought within its precincts a class of residents such as the fathers of the settlement would have wished, are questions which others may attempt to solve. A historian only at times becomes a moral philosopher.

The introduction of the horse car and the stream railroad, passing through Gravesend and yearly conveying increasing crowds to the seashore, finally brought the quiet settlement to the notice of the outside world and aroused it from its sleep of over 200 years.

Brooklyn, too, was steadily filling up the gaps in its own domain and was annually extending its suburban lines, and so the land-boomers got an eye on Gravesend and began to menace its rural life. All that was needed to inaugurate a new condition of things was a rapid and cheap mode of transit, and that was furnished in time by the trolley - the "ubiquitous trolly," as the newspaper reporters used to call it in its early days. The population began to grow with amazing rapidity and new streets were steadily opened in reality or on paper. Old farms were abandoned to the builders, while new settlements, some of them with exceedingly fancy names, spring into existence that put the older settlements like Unionville for a time far in the background, while Sheepshead Bay, which once might have been called Gravesend's suburb, became in reality the center of its life. The popularity of Coney Island reflected itself on Gravesend.

It was the attraction which the land-boomers made most use of to invite settlers, and the closer and more accessible an old farm was to the water front the more quickly was it staked out, its old glory wrecked, and its ancient story wiped out. The new settlers who poured in did not understand the old days, the old methods, and while the shadow of annexation was steadily gathering over the old English town it became the prety of local politicians, some, it is sad to think, claiming, and claiming rightly, descent from original settlers; but most of them of more recent importation, and all of them developing traits of patriotism for "what there is in it." There is no doubt that in its latter days Gravesend, like Flatlands, became the prey of a gang of political spoilsmen, and their acts, as much as anytying else, forced the annexation movement to culminate on July 1, 1894, when Gravesend became a thing of the past and its territory quickly took a place as Brooklyn's Thirty-first Ward.

It is a pity that the last scene in the separate history of Gravesend should be one of riot, bloodshed, comtempt for law, and stern retribution. For several years the leading figure in Gravesend was John Y. McKane.

The history and character of that man are deserving of critical study. He was purely a product of modern American life, and we question if his type, although plentiful enough here, could be produced anywhere else in the wide world.

He was born in county Antrim, Ireland, August 10, 1841, and was brought to this country when a few months old by his mother, his father having preceded them. The family settled at Gravesend, and when sixteen years of age McKane was sent to learn the trade of carpenter.

In 1865 he married Fanny, daughter of Captain C. B. Nostrand, of Gravesend, and in 1866 commenced business on his own account as a bulder and carpenter at Sheepshead Bay. From his twenty-first year he was active in local politics, quickly gathered around him a number of other local workers whose leadership, by making him master of many votes, not only gave him power and influence, but enabled him to extend his business on all sides so as to make him really independent of political emolument. But he believed in holding office, for that in turn gave him political power, and as Supervisor of the town he had often an opportunity of rewarding politically those who were faithful to his fortunes. His influence was made still greater in 1883, for then he was elected President of the Board of Supervisors for Kings county.

At one time he was Gravesend's "Poo Bah," holding the office of Police Commissioner, Chief of Police, President of the Town Board, the Board of Health and the Water Board, - and it is difficult to recall what. His business as a builder continued to flourish, and one could not stand at any point in the old village of Gravesend, at Sheepshead Bay, or along Coney Island without being able, in the new cottages and hotels, to point out handiwork, and good, honest work he did, - of that there is no doubt. His popularity was unbounded. Everyone spoke well of him, and although most people knew him as a politician, and one who was as well versed in the ways and wiles of local politicians as any man living, it was believed that his own hands were clean. He would stand by a supporter through thick and thin, he never repudiated a bargain, broke faith with a friend, or forgot a service. A stanch Democrat, he professed to have the welfare of Gravesend at heart more than the fortunes of his local ticker; but that ticket he always worked for with all his heart. His private life was pure and happy. He had a pleasant home, and there he spent his pleasantest hours. For years he was an active member of the local Methodist Church and the superintendent of its Sabbath-school. Up to a certain point in his career never a word was spoken against him. He was the "boss," he ruled with a rod of iron; he was in all sorts of deals, and it was believed he was thoroughly honest personally and that whatever underhand and shady work he did was done simply in the line of business of the political boss. Most people felt that with all his faults things were safer with him than with any boss who would surely be raised to reign in his stead, - seeing that a boss was necessary. As Gravesend grew in population, as Coney Island year after year added to its visitors by thousands, McKane's position grew in importance, and he had to use all the customary accomplishments of the professional politician to maintain his footing.

The key to his power lay in the ballot-box, and for years it was known that the returns from Gravesend at any election were just as McKane wanted them. There were loud complaints at times of irregularity, but nothing was done, for as usual poliitcal excitement and indignation generally subsided after each election. Then, too, as election after election passed over, McKane became more reckless and defiant of all law. Respect for the law governing elections was especially forgotten by him and cut no figure in all his calculations. There is no doubt that for years the ballots cast in Gravesend were manipulated to suit McKane and his coterie. This in time became so glaring that little more was needed to expose the whole sham and bring it to and end than the zealous protest of some men of determination, and that man came to the front in William J. Gaynor.

In 1893 he was nominated for Justice of the Supreme Court, and when the campaign was on he determined to pay attention to Gravesend, being well aware that McKane was bitterly opposed to him and would stoop to even the most desperate act to accomplish his defeat. He determined to have at least an hones vote in Gravesend, and to that end obtained an order from the Supreme Court compelling the Registrars of Elections to produce the registry books; but the books could not be found. On election day twelve watchers sent by Gaynor went to Gravesend armed with an injunction from the Supreme Court forbidding McKane or any one else from interfering with them; but McKane, folding his arms behind his back, refused to touch the document, uttering the memorable words, "Injunctions don't go here."

Colonel Alexander S. Bacon and the other watchers were arrested, some were maltreated brutally, and all were glad to get back to Brooklyn. Gravesend had 6,000 votes registered, while her population should only have shown some 2,000. The votes cast were 3,500, proving that in spite of all the excitement, fraudulent methods had been at work. American citizens can stand a good deal; they can be plundered, imposed upon and deluded by politicians year out and year in with impunity. Every now and again then they arise in their might and "turn the rascals out," but they soon forget their indignation, the rascals return to their plunder, and things go on as before. But there is one thing the people will neither condone nor forget, and that is tampering with the ballot-box, the foundation of all their liberties, and the united voice of a free people.

Of the 3,500 votes cast, Gaynor received an insignificant number, but the general returns showed that he was elected to the bench by a large majority. Public attention as to affairs in Gravesend had been aroused, the flagrant tinkering with the ballot-box and the insults and indignities and maltreatment of those who represented the law created a deep feeling of resentment in the community, and a demand arose for the prosecution of the offenders. A fund was raised to bring the matter to an issue, and McKane and several of his prominent associates were indicted. As a result of his trial McKane was convicted of violating the election law, and on February 19, 1894, sentenced by Justice Bartlett to six years in state prison. After a few delays, trying to evade the sentence by legal quibbles, he began his tern in Sing Sing on March 2, following, and was there incarcerated, "a model prisoner," the keepers said, until April 30, 1898, having then finished his term less the deduction allowed to all prisoners who behave themselves as behavior is understood in penal institutions.

He emerged from prison a broken-down man in every way, and did not even attempt to regain his old-time grip. His once indomitable spirit was crushed beneath the terrible blow which had transformed him fron "a useful citizen" into a convict, and he died, broken-hearted, September 5, 1899.

McKane was not the only one who suffered for the "crime of Gravesend," as the reporters put it. Many of his supporters suffered imprisonment and fine, and most noted being Kenneth E. Sutherland, sent to prison for one year and fined $500 on one count and sentenced to another year's imprisonment on a fresh chage: R. V. B. Newton, sentenced to nine month's imprisonment and $750 fine; A. S. Jameson eighteen months; M. P. Ryan, four months and $500; F. Bader, five months and so on down to comparatively petty sentences, for the less conspicious workers of the gang.

Possibly the full extent of the frauds at the ballot-boxes was not realized by the public until the election at Gravesend in April, 1894, when, under honest auspices, only 1,928 votes were cast.

Thus closed in turmoil and gloom the story of a town founded in righteousness and honesty, and distinguised for its uprightness and the even tenor of its ways. It demonstrated the unscrupulousness of politics and the rottenness which can be introduced into our municipal government by a few men who are zealous for power. No one pitied McKane and his fellows, and their fate has been held to be a significant and much-needed lesson to others who might be induced to drift into such methods; and drift is the right word. McKane and his associates were not bad men; in private life most of them were above reproach; but they drifted along the current of low political intrigue until, blind to the results, they "shot Niagara," went beyond the safeguards of law and order, defied these in fact, and landed in prison cells. Their story is a blot on American politics, and it is a pity that the records of Gravesend should close with the details of a political crime and its salutary punishment.